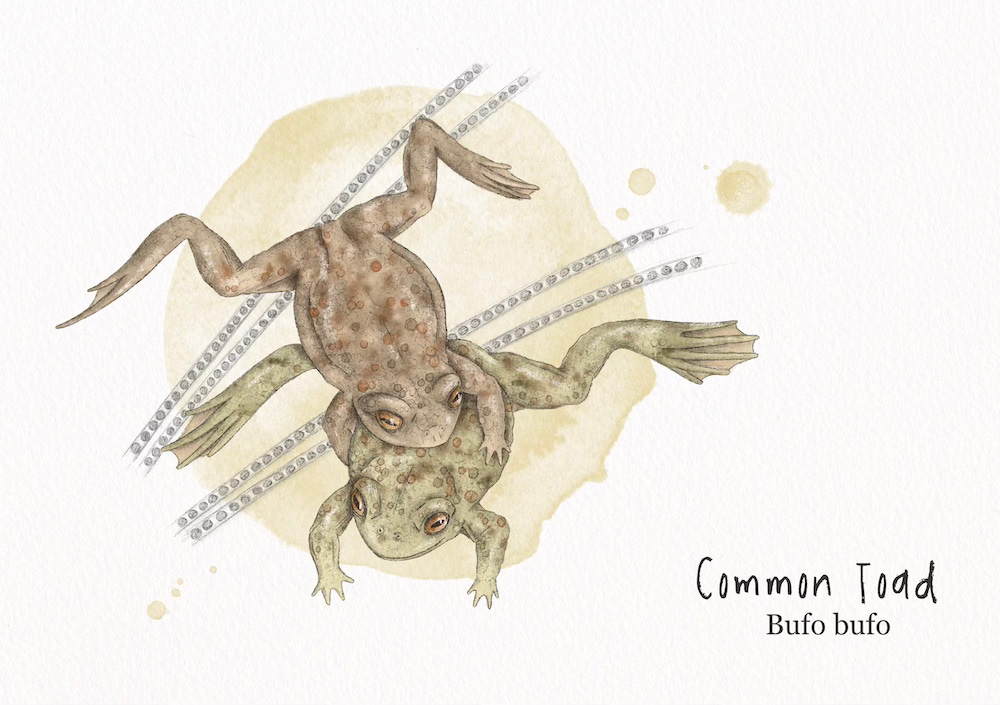

Amplexus

In addition to my semi-regular ramblings about art angst, once a month I’ll be focusing on a different animal that I have encountered. This month I'm talking toads.

Spring arrived suddenly this year, as if one day I was in the grip of winter, huddled under a heated blanket at my desk, and the next, I was searching for my sunglasses and worrying I hadn’t used enough sunscreen. Almost overnight, the daffodils appeared and the trees developed that delicate green haze that indicates they’re about to burst into life again.

The most noticeable difference for me (aside from almost collapsing from heat stroke as I stupidly wore my winter coat on the school run), was that the geese were gone and I didn’t see them leave. Every year tens of thousands of pink-footed geese migrate to the UK from Iceland, Greenland and Svalbard to spend the winter feeding on our fields and wetlands. While here they make a twice-daily commute over my house and at the end of winter, their numbers peak as they’re joined by birds who spent their winters in South East England. On some evenings the sky can fill with the sight and sound of geese as skein after skein gather on the mudflats before leaving for their summer breeding grounds.

But not this year. This year the geese just disappeared. They slipped away quietly one morning without their usual fanfare and I didn’t notice until they were gone. I did however, see one sign of spring that I haven’t witnessed in several years - Amplexus.

Amplexus, from the Latin “embrace”, describes the behaviour of male frogs and toads as they cling to the backs of the larger females during mating. They can remain in this position for many hours and it’s not uncommon to find one female with a number of males forming a mating ball around her. A couple of weeks ago, we visited the large pond on our usual walk through the woods. It initially seemed lifeless except for a pair of mallards who came to greet us, then a movement in the shallows, and another and soon we were spotting dozens of toad couples. Females wearing males like little backpacks and using their powerful hind legs to kick away other unwanted suitors. We realised that the faint quacking of distant mallards that had barely registered when we’d arrived, was actually the chirping of the toads. And there were already strands of the black beaded spawn in amongst the vegetation. In as little as ten days, tadpoles would start to emerge.

Most of the toads in that pond will have been born there and may have travelled up to a kilometre to make the journey back to breed, which is a huge distance for such a small animal moving at a steady crawl. We were especially pleased to see them this year as, for the past six years, we hadn’t seen a single breeding toad in the pond.

We’d been looking for them every year since the day we stumbled upon the amphibian bonanza. Usually toads breed later in the year than frogs, but on this particular year, probably driven by the weather, both were mating at the same time. For some reason, perhaps natural cycles in population numbers, there was an unbelievable amount of both species. We could hear the chorus of calls long before we reached the pond and when we did, the water seemed to bubble with the movement of so many animals. It was a mating frenzy as males tussled and grabbed and fiercely defended their females. We watched for hours, in awe at the dramas being played out in a pond that generally appears a little swampy and lifeless.

Whenever we see frogs or toads or their spawn now, we can’t help but refer to the spectacle of that year’s amphibian orgy. It was probably not normal occurrence that we’ve simply missed in recent years, but more likely a combination of a colder winter, a damp night, a full moon, and other unknown factors, that led to their being so many frogs and toads gathered there that single day. Either way, it’s a memory of a common and familiar little animal that will stay with me.

If, like me, you are even remotely trypophobic, be very careful searching the internet for images relating to toad breeding behaviour! You might accidentally be exposed to the Surinam toad. Trust me, you’ll want to avoid this one.

I noticed that our geese disappeared without any fanfare too. I usually see great flocks of hundreds in March. This year there were none :(

There’s something peculiarly exciting about encountering a toad or frog. When I was a kid my grandad used to have a toad that lived under his greenhouse in North London. Lovely creatures. M